Archbishop Cranmer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Letter from Cranmer on Henry VIII's divorce

at the Center for Medieval Studies at

Thirty-Nine Articles

from the Anglican Communion official website * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cranmer, Thomas 1489 births 1556 deaths 16th-century Christian saints 16th-century English bishops 16th-century Protestant martyrs Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge Alumni of Magdalene College, Cambridge Anglican saints Archbishops of Canterbury Christianity in Oxford Converts to Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism Critics of the Catholic Church Doctors of Divinity English Anglican theologians English Anglicans English Calvinist and Reformed theologians Executed English people Executed people from Nottinghamshire Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge Founders of religions People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People executed by the Kingdom of England by burning People executed for heresy People executed under Mary I of England Prisoners in the Tower of London Protestant martyrs of England Protestant Reformers 16th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 15th-century Anglican theologians 16th-century Anglican theologians

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the

Cranmer was born in 1489 at

Cranmer was born in 1489 at

Cranmer's first contact with a Continental reformer was with

Cranmer's first contact with a Continental reformer was with

For the next few months, Cranmer and the king worked on establishing legal procedures on how the monarch's marriage would be judged by his most senior clergy. Several drafts of the procedures have been preserved in letters written between the two. Once procedures were agreed upon, Cranmer opened court sessions on 10 May, inviting Henry and Catherine of Aragon to appear. Gardiner represented the king; Catherine did not appear or send a proxy. On 23 May Cranmer pronounced the judgement that Henry's marriage with Catherine was against the law of God. He even issued a threat of

For the next few months, Cranmer and the king worked on establishing legal procedures on how the monarch's marriage would be judged by his most senior clergy. Several drafts of the procedures have been preserved in letters written between the two. Once procedures were agreed upon, Cranmer opened court sessions on 10 May, inviting Henry and Catherine of Aragon to appear. Gardiner represented the king; Catherine did not appear or send a proxy. On 23 May Cranmer pronounced the judgement that Henry's marriage with Catherine was against the law of God. He even issued a threat of

Cranmer was not immediately accepted by the bishops within his province. When he attempted a

Cranmer was not immediately accepted by the bishops within his province. When he attempted a

The setback for the reformers was short-lived. By September, Henry was displeased with the results of the Act and its promulgators; the ever-loyal Cranmer and Cromwell were back in favour. The king asked his archbishop to write a new preface for the

The setback for the reformers was short-lived. By September, Henry was displeased with the results of the Act and its promulgators; the ever-loyal Cranmer and Cromwell were back in favour. The king asked his archbishop to write a new preface for the

With the atmosphere in Cranmer's favour, he pursued quiet efforts to reform the Church, particularly the liturgy. On 27 May 1544 the first officially authorised vernacular service was published, the processional service of intercession known as the ''

With the atmosphere in Cranmer's favour, he pursued quiet efforts to reform the Church, particularly the liturgy. On 27 May 1544 the first officially authorised vernacular service was published, the processional service of intercession known as the ''

Under the regency of Seymour, the reformers became part of the establishment. A royal visitation of the provinces took place in August 1547 and each parish that was visited was instructed to obtain a copy of the ''Homilies''. This book consisted of twelve homilies of which four were written by Cranmer. His reassertion of the doctrine of justification by faith elicited a strong reaction from Gardiner. In the "Homily of Good Works annexed to Faith", Cranmer attacked

Under the regency of Seymour, the reformers became part of the establishment. A royal visitation of the provinces took place in August 1547 and each parish that was visited was instructed to obtain a copy of the ''Homilies''. This book consisted of twelve homilies of which four were written by Cranmer. His reassertion of the doctrine of justification by faith elicited a strong reaction from Gardiner. In the "Homily of Good Works annexed to Faith", Cranmer attacked

As the use of English in worship services spread, the need for a complete uniform liturgy for the Church became evident. Initial meetings to start what would eventually become the 1549 ''Book of Common Prayer'' were held in the former abbey of Chertsey and in

As the use of English in worship services spread, the need for a complete uniform liturgy for the Church became evident. Initial meetings to start what would eventually become the 1549 ''Book of Common Prayer'' were held in the former abbey of Chertsey and in

The first result of co-operation and consultation between Cranmer and Bucer was the Ordinal, the liturgy for the ordination of priests. This was missing in the first Prayer Book and was not published until 1550. Cranmer adopted Bucer's draft and created three services for commissioning a deacon, a priest, and a bishop. In the same year, Cranmer produced the '' Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ'', a semi-official explanation of the eucharistic theology within the Prayer Book. It was the first full-length book to bear Cranmer's name on the title-page. The preface summarises his quarrel with Rome in a well-known passage where he compared "beads, pardons, pilgrimages, and such other like popery" with weeds, but the roots of the weeds were transubstantiation, the corporeal real presence, and the sacrificial nature of the mass.

Although Bucer assisted in the development of the English Reformation, he was still quite concerned about the speed of its progress. Both Bucer and Fagius had noticed that the 1549 Prayer Book was not a remarkable step forward, although Cranmer assured Bucer that it was only a first step and that its initial form was only temporary. By late 1550, Bucer was becoming disillusioned. Cranmer made sure that he did not feel alienated and kept in close touch with him. This attention paid off during the

The first result of co-operation and consultation between Cranmer and Bucer was the Ordinal, the liturgy for the ordination of priests. This was missing in the first Prayer Book and was not published until 1550. Cranmer adopted Bucer's draft and created three services for commissioning a deacon, a priest, and a bishop. In the same year, Cranmer produced the '' Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ'', a semi-official explanation of the eucharistic theology within the Prayer Book. It was the first full-length book to bear Cranmer's name on the title-page. The preface summarises his quarrel with Rome in a well-known passage where he compared "beads, pardons, pilgrimages, and such other like popery" with weeds, but the roots of the weeds were transubstantiation, the corporeal real presence, and the sacrificial nature of the mass.

Although Bucer assisted in the development of the English Reformation, he was still quite concerned about the speed of its progress. Both Bucer and Fagius had noticed that the 1549 Prayer Book was not a remarkable step forward, although Cranmer assured Bucer that it was only a first step and that its initial form was only temporary. By late 1550, Bucer was becoming disillusioned. Cranmer made sure that he did not feel alienated and kept in close touch with him. This attention paid off during the

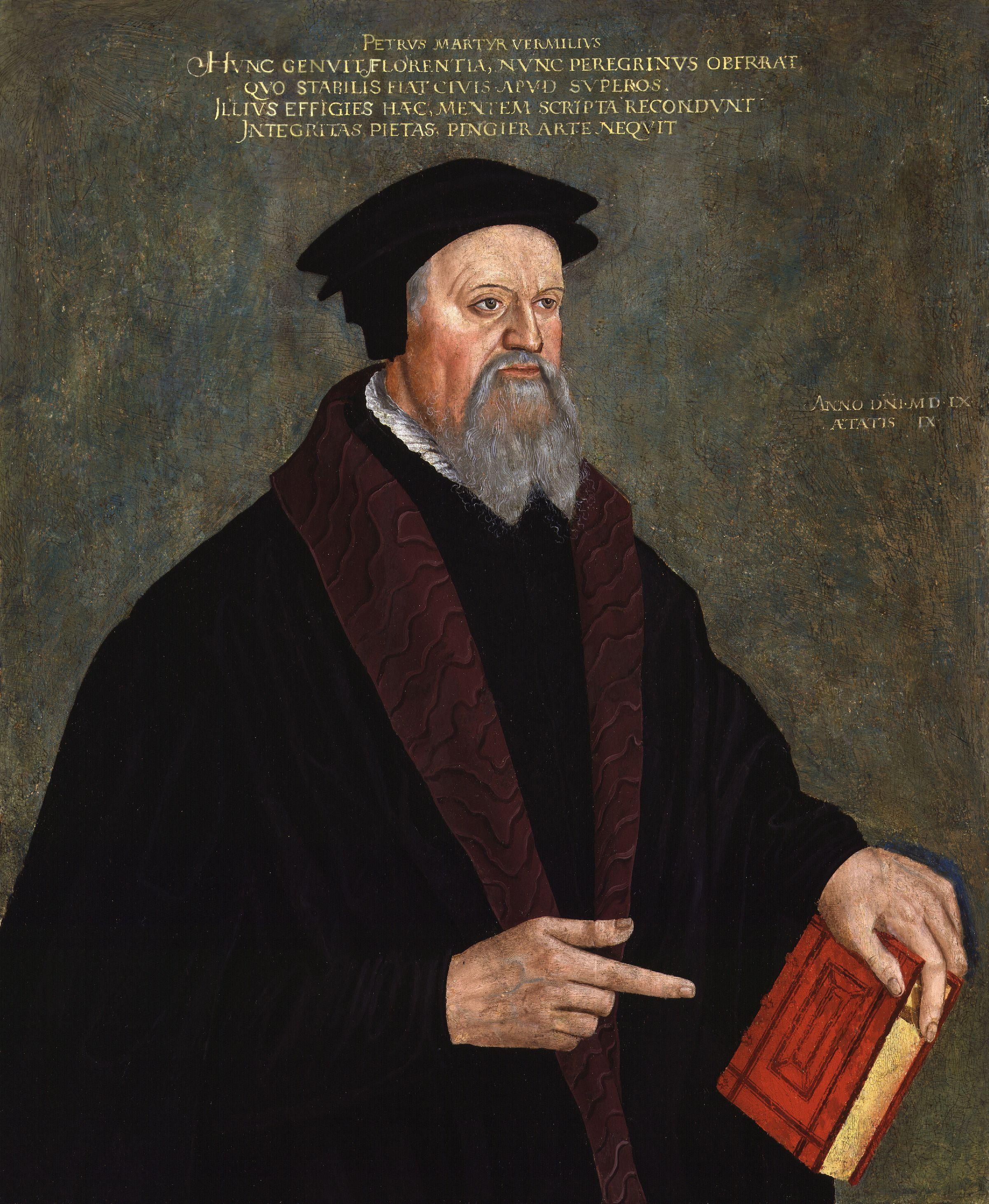

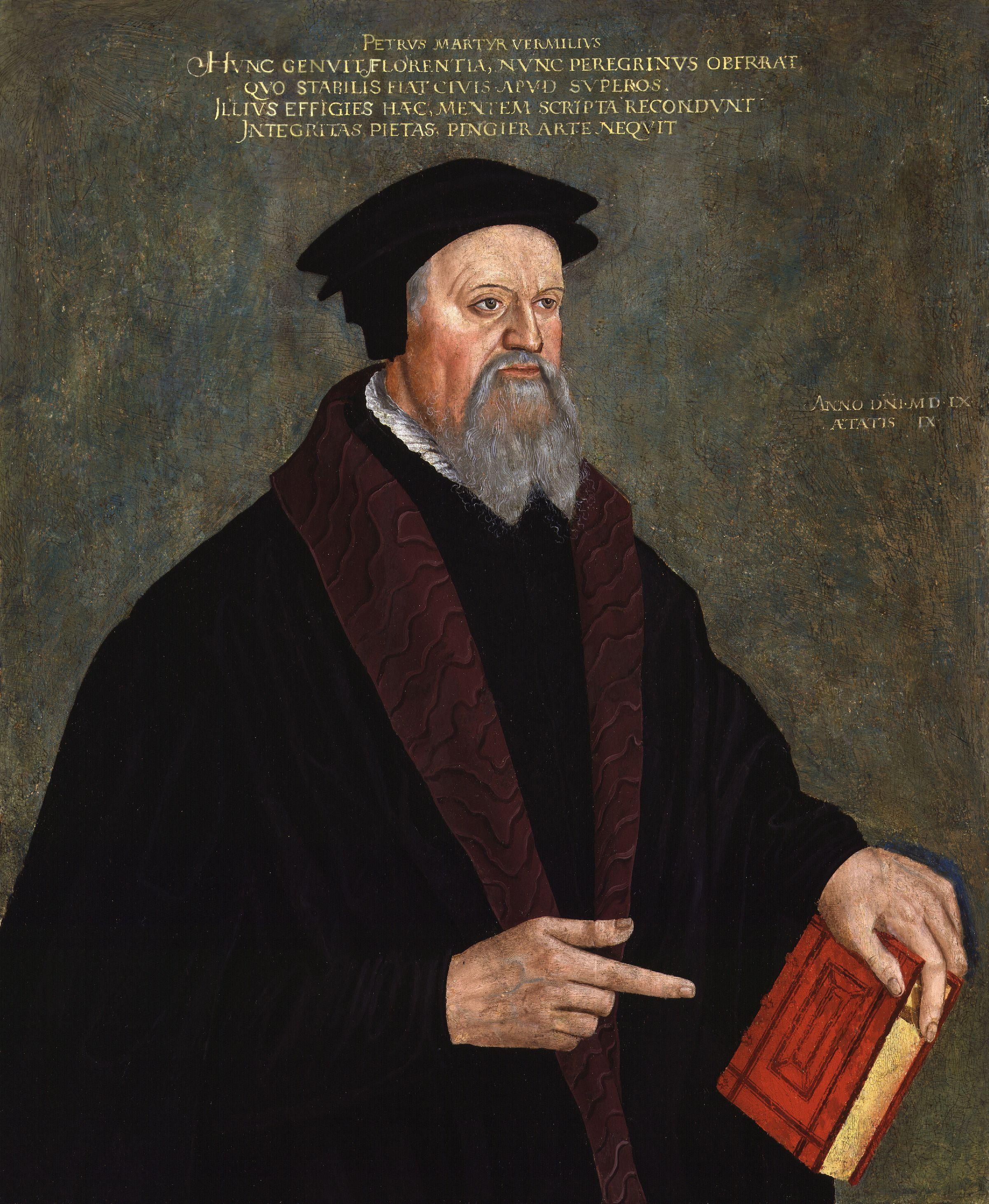

The original Catholic canon law that defined governance within the Church clearly needed revision following Henry's break with Rome. Several revision attempts were made throughout Henry's reign, but these initial projects were shelved as the speed of reform outpaced the time required to work on a revision. As the reformation stabilised, Cranmer formed a committee in December 1551 to restart the work. He recruited Peter Martyr to the committee and he also asked Łaski and Hooper to participate, showing his habitual ability to forgive past actions. Cranmer and Martyr realised that a successful enactment of a reformed ecclesiastical law-code in England would have international significance. Cranmer planned to draw together all the reformed churches of Europe under England's leadership to counter the

The original Catholic canon law that defined governance within the Church clearly needed revision following Henry's break with Rome. Several revision attempts were made throughout Henry's reign, but these initial projects were shelved as the speed of reform outpaced the time required to work on a revision. As the reformation stabilised, Cranmer formed a committee in December 1551 to restart the work. He recruited Peter Martyr to the committee and he also asked Łaski and Hooper to participate, showing his habitual ability to forgive past actions. Cranmer and Martyr realised that a successful enactment of a reformed ecclesiastical law-code in England would have international significance. Cranmer planned to draw together all the reformed churches of Europe under England's leadership to counter the

In his final days Cranmer's circumstances changed, which led to several

In his final days Cranmer's circumstances changed, which led to several  Cranmer was told that he would be able to make a final recantation, but that this time it was to be in public during a service at the University Church. He wrote and submitted the speech in advance and it was published after his death. At the pulpit on the day of his execution, 21 March 1556, he opened with a prayer and an exhortation to obey the king and queen, but he ended his sermon totally unexpectedly, deviating from the prepared script. He renounced the recantations that he had written or signed with his own hand since his degradation and he stated that, in consequence, his hand would be punished by being burnt first. He then said, "And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ's enemy, and

Cranmer was told that he would be able to make a final recantation, but that this time it was to be in public during a service at the University Church. He wrote and submitted the speech in advance and it was published after his death. At the pulpit on the day of his execution, 21 March 1556, he opened with a prayer and an exhortation to obey the king and queen, but he ended his sermon totally unexpectedly, deviating from the prepared script. He renounced the recantations that he had written or signed with his own hand since his degradation and he stated that, in consequence, his hand would be punished by being burnt first. He then said, "And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ's enemy, and

Cranmer's family had been exiled to the Continent in 1539. It is not known exactly when they returned to England, but it was soon after the accession of Edward VI in 1547 that Cranmer publicly acknowledged their existence. Not much is known about the early years of the children. His daughter, Margaret, was likely born in the 1530s and his son, Thomas, came later, probably during the reign of Edward. Around the time of Mary's accession, Cranmer's wife, Margarete, escaped to Germany, while his son was entrusted to his brother, Edmund Cranmer, who took him to the Continent. Margarete Cranmer eventually married Cranmer's favourite publisher,

Cranmer's family had been exiled to the Continent in 1539. It is not known exactly when they returned to England, but it was soon after the accession of Edward VI in 1547 that Cranmer publicly acknowledged their existence. Not much is known about the early years of the children. His daughter, Margaret, was likely born in the 1530s and his son, Thomas, came later, probably during the reign of Edward. Around the time of Mary's accession, Cranmer's wife, Margarete, escaped to Germany, while his son was entrusted to his brother, Edmund Cranmer, who took him to the Continent. Margarete Cranmer eventually married Cranmer's favourite publisher,

The execution of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1556)

at EnglishHistory.net

Thomas Cranmer biography

at the

English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

and Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

during the reigns of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

and, for a short time, Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

, which was one of the causes of the separation of the English Church from union with the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

. Along with Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charge ...

, he supported the principle of royal supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the Eng ...

, in which the king was considered sovereign over the Church within his realm.

During Cranmer's tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury, he was responsible for establishing the first doctrinal and liturgical structures of the reformed Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. Under Henry's rule, Cranmer did not make many radical changes in the Church, due to power struggles between religious conservatives and reformers. He published the first officially authorised vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

service, the ''Exhortation and Litany

The ''Exhortation and Litany'', published in 1544, is the earliest officially authorized vernacular service in English. The same rite survives, in modified form, in the ''Book of Common Prayer''.

Background

Before the English Reformation, process ...

''.

When Edward came to the throne, Cranmer was able to promote major reforms. He wrote and compiled the first two editions of the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'', a complete liturgy for the English Church. With the assistance of several Continental reformers to whom he gave refuge, he changed doctrine or discipline in areas such as the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

, clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because the ...

, the role of images

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensiona ...

in places of worship, and the veneration

Veneration ( la, veneratio; el, τιμάω ), or veneration of saints, is the act of honoring a saint, a person who has been identified as having a high degree of sanctity or holiness. Angels are shown similar veneration in many religions. Etymo ...

of saints. Cranmer promulgate

Promulgation is the formal proclamation or the declaration that a new statutory or administrative law is enacted after its final approval. In some jurisdictions, this additional step is necessary before the law can take effect.

After a new law ...

d the new doctrines through the Prayer Book, the ''Homilies

A homily (from Greek ὁμιλία, ''homilía'') is a commentary that follows a reading of scripture, giving the "public explanation of a sacred doctrine" or text. The works of Origen and John Chrysostom (known as Paschal Homily) are considered ex ...

'' and other publications.

After the accession of the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Mary I, Cranmer was put on trial for treason and heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. Imprisoned for over two years and under pressure from Church authorities, he made several recantation

Recantation means a personal public act of denial of a previously published opinion or belief. It is derived from the Latin "''re cantare''", to re-sing.

Philosophy

Philosophically recantation is linked to a genuine change of opinion, often ...

s and apparently reconciled himself with the Catholic Church. While this would have normally absolved him, Mary wanted him executed, and, on the day of his execution, he withdrew his recantations, to die a heretic to Catholics and a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

for the principles of the English Reformation. Cranmer's death was immortalised in ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engli ...

'' and his legacy lives on within the Church of England through the ''Book of Common Prayer'' and the ''Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

'', an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

statement of faith derived from his work.

Origins

Cranmer was born in 1489 at

Cranmer was born in 1489 at Aslockton

Aslockton is an English village and civil parish 12 miles (19.3 km) east of Nottingham and two miles (3.2 km) east of Bingham, on the north bank of the River Smite opposite Whatton-in-the-Vale. The parish is also adjacent to Scarring ...

in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

, England. He was a younger son of Thomas Cranmer by his wife Agnes Hatfield. Thomas Cranmer was of modest wealth but was from a well-established armigerous

In heraldry, an armiger is a person entitled to use a heraldic achievement (e.g., bear arms, an "armour-bearer") either by hereditary right, grant, matriculation, or assumption of arms. Such a person is said to be armigerous. A family or a cl ...

gentry family which took its name from the manor of Cranmer in Lincolnshire. A ledger stone

A ledger stone or ledgerstone is an inscribed stone slab usually laid into the floor of a church to commemorate or mark the place of the burial of an important deceased person. The term "ledger" derives from the Middle English words ''lygger'', ' ...

to one of his relatives in the Church of St John of Beverley, Whatton

The Church of St John of Beverley, Whatton is a parish church in the Church of England in Whatton-in-the-Vale, Nottinghamshire, dedicated to St John of Beverley. The church is Grade II* listed by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media an ...

, near Aslockton is inscribed as follows: ''Hic jacet Thomas Cranmer, Armiger, qui obiit vicesimo septimo die mensis Maii, anno d(omi)ni. MD centesimo primo, cui(us) a(n)i(ma)e p(ro)p(i)cietur Deus Amen'' ("here lies Thomas Cranmer, Esquire, who died on the 27th day of May in the year of our lord 1601, on whose soul may God look upon with mercy"). The arms of the Cranmer and Aslockton families are displayed. The figure is that of a man in flowing hair and gown, and a purse at his right side. Their oldest son, John Cranmer, inherited the family estate, whereas Thomas and his younger brother Edmund were placed on the path to a clerical career.

Early years (1489–1527)

Historians know nothing definite about Cranmer's early schooling. He probably attended a grammar school in his village. At the age of 14, two years after the death of his father, he was sent to the newly createdJesus College, Cambridge

Jesus College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's full name is The College of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist and the glorious Virgin Saint Radegund, near Cambridge. Its common name comes fr ...

. It took him eight years to attain his Bachelor of Arts degree, following a curriculum of logic, classical literature and philosophy. During this time, he began to collect medieval scholastic books, which he preserved faithfully throughout his life. For his master's degree he studied the humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

, Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples

Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples ( Latinized as Jacobus Faber Stapulensis; c. 1455 – c. 1536) was a French theologian and a leading figure in French humanism. He was a precursor of the Protestant movement in France. The "d'Étaples" was not part of ...

and Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

. He finished the course in three years. Shortly after receiving his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree in 1515, he was elected to a Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

ship of Jesus College.

Sometime after Cranmer took his MA, he married a woman named Joan. Although he was not yet a priest, he was obliged to give up his fellowship, resulting in the loss of his residence at Jesus College. To support himself and his wife, he took a job as a reader

A reader is a person who reads. It may also refer to:

Computing and technology

* Adobe Reader (now Adobe Acrobat), a PDF reader

* Bible Reader for Palm, a discontinued PDA application

* A card reader, for extracting data from various forms of ...

at Buckingham Hall (later reformed as Magdalene College

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

). When Joan died during her first childbirth, Jesus College showed its regard for Cranmer by reinstating his fellowship. He began studying theology and by 1520 he had been ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

, the university already having named him as one of its preachers. He received his Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (D.D. or DDiv; la, Doctor Divinitatis) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity.

In the United Kingdom, it is considered an advanced doctoral degree. At the University of Oxford, doctors of divinity are ran ...

degree in 1526.

Not much is known about Cranmer's thoughts and experiences during his three decades at Cambridge. Traditionally, he has been portrayed as a humanist whose enthusiasm for biblical scholarship prepared him for the adoption of Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

ideas, which were spreading during the 1520s. A study of his marginalia reveals an early antipathy to Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

and an admiration for Erasmus. When Cardinal Wolsey, the king's Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, selected several Cambridge scholars, including Edward Lee, Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was b ...

and Richard Sampson

Richard Sampson (died 25 September 1554) was an English clergyman and composer of sacred music, who was Anglican bishop of Chichester and subsequently of Coventry and Lichfield.

Biography

He was educated at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, the Paris S ...

, to be diplomats throughout Europe, Cranmer was chosen for an embassy to the Holy Roman Emperor. His supposed participation in an earlier embassy to Spain, mentioned in the older literature, has proved to be spurious.

In the service of Henry VIII (1527–1532)

Henry VIII's first marriage had its origins in 1502 when his elder brother,Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brittonic languages, Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. An ...

, died. Their father, Henry VII, then betrothed Arthur's widow, Catherine of Aragon, to the future king. The betrothal immediately raised questions related to the biblical prohibition (in Leviticus 18 and 20) against marriage to a brother's wife. The couple married in 1509 and after a series of miscarriages, a daughter, Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, was born in 1516. By the 1520s, Henry still did not have a son to name as heir and he took this as a sure sign of God's anger and made overtures to the Vatican about an annulment

Annulment is a legal procedure within Law, secular and Religious law, religious legal systems for declaring a marriage Void (law), null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually ex post facto law, retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is c ...

. He gave Cardinal Wolsey the task of prosecuting his case; Wolsey began by consulting university experts. From 1527, in addition to his duties as a Cambridge don, Cranmer assisted with the annulment proceedings.

In mid-1529, Cranmer stayed with relatives in Waltham Holy Cross

Waltham Abbey is a civil parish in Epping Forest District in Essex, England. Located approximately north-northeast of central London and adjacent to the Greater London boundary, it is a partly urbanised parish with large sections of open land ...

to avoid an outbreak of the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

in Cambridge. Two of his Cambridge associates, Stephen Gardiner and Edward Foxe

Edward Foxe (c. 1496 – 8 May 1538) was an English churchman, Bishop of Hereford. He played a major role in Henry VIII's divorce from Catherine of Aragon, and he assisted in drafting the '' Ten Articles'' of 1536.

Early life

He was born at ...

, joined him. The three discussed the annulment issue and Cranmer suggested putting aside the legal case in Rome in favour of a general canvassing of opinions from university theologians throughout Europe. Henry showed much interest in the idea when Gardiner and Foxe presented him this plan. It is not known whether the king or his new Lord Chancellor, Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, explicitly approved the plan. Eventually it was implemented and Cranmer was requested to join the royal team in Rome to gather opinions from the universities. Edward Foxe coordinated the research effort and the team produced the '' Collectanea Satis Copiosa'' ("The Sufficiently Abundant Collections") and ''The Determinations'', historical and theological support for the argument that the king exercised supreme jurisdiction within his realm.

Cranmer's first contact with a Continental reformer was with

Cranmer's first contact with a Continental reformer was with Simon Grynaeus

Simon Grynaeus (born Simon Griner; 1493 – 1 August 1541) was a German scholar and theologian of the Protestant Reformation.

Biography

Grynaeus was the son of Jacob Gryner, a Swabian peasant, and was born at Veringendorf, in Hohenzollern-Sigma ...

, a humanist based in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, Switzerland, and a follower of the Swiss reformers, Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

and Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius (also ''Œcolampadius'', in German also Oekolampadius, Oekolampad; 1482 – 24 November 1531) was a German Protestant reformer in the Calvinist tradition from the Electoral Palatinate. He was the leader of the Protestant ...

. In mid-1531, Grynaeus took an extended visit to England to offer himself as an intermediary between the king and the Continental reformers. He struck up a friendship with Cranmer and after his return to Basel, he wrote about Cranmer to the German reformer Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer ( early German: ''Martin Butzer''; 11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a me ...

in Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

. Grynaeus' early contacts initiated Cranmer's eventual relationship with the Strasbourg and Swiss reformers.

In January 1532, Cranmer was appointed the resident ambassador at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

. As the emperor travelled throughout his realm, Cranmer had to follow him to his residence in Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

. He passed through the Lutheran city of Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

and saw for the first time the effects of the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. When the Imperial Diet was moved to Nuremberg, he met the leading architect of the Nuremberg reforms, Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander (; 19 December 1498 – 17 October 1552) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Career

Born at Gunzenhausen, Ansbach, in the region of Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before b ...

. They became good friends, and during that July Cranmer took the surprising action of marrying Margarete

Margarete is a German feminine given name. It is derived from Ancient Greek ''margarites'' (μαργαρίτης), meaning "the pearl". Via the Latin ''margarita'', it arrived in the German sprachraum. Related names in English include Daisy, Gre ...

, the niece of Osiander's wife. He did not take her as his mistress, as was the prevailing custom with priests for whom celibacy was too rigorous. Scholars note that Cranmer had moved, however moderately at this stage, into identifying with certain Lutheran principles. This progress in his personal life was not matched in his political life as he was unable to persuade Charles, Catherine's nephew, to support the annulment of his aunt's marriage.

Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury (1532–1534)

While Cranmer was following Charles through Italy, he received a royal letter dated 1 October 1532 informing him that he had been appointed the new Archbishop of Canterbury, following the death of archbishopWilliam Warham

William Warham ( – 22 August 1532) was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1503 to his death.

Early life and education

Warham was the son of Robert Warham of Malshanger in Hampshire. He was educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford ...

. Cranmer was ordered to return to England. The appointment had been secured by the family of Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

, who was being courted by Henry. When Cranmer's promotion became known in London, it caused great surprise as Cranmer had previously held only minor positions in the Church. Cranmer left Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

on 19 November and arrived in England at the beginning of January. Henry personally financed the papal bulls necessary for Cranmer's promotion to Canterbury. The bulls were easily acquired because the papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international org ...

was under orders from Rome to please the English in an effort to prevent a final breach. The bulls arrived around 26 March 1533 and Cranmer was consecrated as a bishop on 30 March in St Stephen's Chapel, by John Longland

John Longland (1473 – 7 May 1547) was the English Dean of Salisbury from 1514 to 1521 and Bishop of Lincoln from 1521 to his death in 1547.

Career

He was made a Demy at Magdalen College, Oxford in 1491 and became a Fellow. He was King Henry ...

, Bishop of Lincoln

The Bishop of Lincoln is the ordinary (diocesan bishop) of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.

The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and ...

; John Vesey

John Vesey or Veysey ( – 23 October 1554) was Bishop of Exeter from 1519 until his death in 1554, having been briefly deposed 1551–3 by King Edward VI for his opposition to the Reformation.

Origins

He was born (as "John Harman"), probabl ...

, Bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. Since 30 April 2014 the ordinary has been Robert Atwell.

; and Henry Standish

Henry Standish (c. 1475–1535) was an English Franciscan, who became Bishop of St. Asaph. He is known as an opponent of Erasmus in particular, and humanists in general.

He was a Doctor of Divinity of the University of Oxford. He was Guardian of ...

, Bishop of St Asaph. Even while they were waiting for the bulls, Cranmer continued to work on the annulment proceedings, which required greater urgency after Anne announced her pregnancy. Henry and Anne were secretly married on 24 or 25 January 1533 in the presence of a handful of witnesses. Cranmer did not learn of the marriage until 14 days later.

For the next few months, Cranmer and the king worked on establishing legal procedures on how the monarch's marriage would be judged by his most senior clergy. Several drafts of the procedures have been preserved in letters written between the two. Once procedures were agreed upon, Cranmer opened court sessions on 10 May, inviting Henry and Catherine of Aragon to appear. Gardiner represented the king; Catherine did not appear or send a proxy. On 23 May Cranmer pronounced the judgement that Henry's marriage with Catherine was against the law of God. He even issued a threat of

For the next few months, Cranmer and the king worked on establishing legal procedures on how the monarch's marriage would be judged by his most senior clergy. Several drafts of the procedures have been preserved in letters written between the two. Once procedures were agreed upon, Cranmer opened court sessions on 10 May, inviting Henry and Catherine of Aragon to appear. Gardiner represented the king; Catherine did not appear or send a proxy. On 23 May Cranmer pronounced the judgement that Henry's marriage with Catherine was against the law of God. He even issued a threat of excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

if Henry did not stay away from Catherine. Henry was now free to marry and, on 28 May, Cranmer validated Henry and Anne's marriage. On 1 June, Cranmer personally crowned and anointed Anne queen and delivered to her the sceptre and rod. Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

was furious at this defiance, but he could not take decisive action as he was pressured by other monarchs to avoid an irreparable breach with England. On 9 July he provisionally excommunicated Henry and his advisers (who included Cranmer) unless he repudiated Anne by the end of September. Henry kept Anne as his wife and, on 7 September, Anne gave birth to Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

. Cranmer baptised

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

her immediately afterwards and acted as one of her godparents.

It is difficult to assess how Cranmer's theological views had evolved since his Cambridge days. There is evidence that he continued to support humanism; he renewed Erasmus' pension that had previously been granted by Archbishop Warham. In June 1533, he was confronted with the difficult tasks not only of disciplining a reformer, but also of seeing him burned at the stake. John Frith was condemned to death for his views on the eucharist: he denied the real presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

There are a number of Christian denominati ...

. Cranmer personally tried to persuade him to change his views without success. Although he rejected Frith's radicalism, by 1534 he clearly signalled that he had broken with Rome and that he had set a new theological course. He supported the cause of reform by gradually replacing the old guard in his ecclesiastical province

An ecclesiastical province is one of the basic forms of jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United State ...

with men such as Hugh Latimer

Hugh Latimer ( – 16 October 1555) was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester during the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary I he was burned at the ...

who followed the new thinking. He intervened in religious disputes, supporting reformers, to the disappointment of religious conservatives who desired to maintain the link with Rome.

Under the vicegerency (1535–1538)

Cranmer was not immediately accepted by the bishops within his province. When he attempted a

Cranmer was not immediately accepted by the bishops within his province. When he attempted a canonical visitation

In the Catholic Church, a canonical visitation is the act of an ecclesiastical superior who in the discharge of his office visits persons or places with a view to maintaining faith and discipline and of correcting abuses. A person delegated to car ...

, he had to avoid locations where a resident conservative bishop might make an embarrassing personal challenge to his authority. In 1535, Cranmer had difficult encounters with several bishops, John Stokesley

John Stokesley (8 September 1475 – 8 September 1539) was an English clergyman who was Bishop of London during the reign of Henry VIII.

Life

Stokesley was born at Collyweston in Northamptonshire, and became a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford ...

, John Longland

John Longland (1473 – 7 May 1547) was the English Dean of Salisbury from 1514 to 1521 and Bishop of Lincoln from 1521 to his death in 1547.

Career

He was made a Demy at Magdalen College, Oxford in 1491 and became a Fellow. He was King Henry ...

, and Stephen Gardiner among others. They objected to Cranmer's power and title and argued that the Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the En ...

did not define his role. This prompted Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charge ...

, the king's chief minister, to activate and to take the office of the vicegerent

Vicegerent is the official administrative deputy of a ruler or head of state: ''vice'' (Latin for "in place of") and ''gerere'' (Latin for "to carry on, conduct").

In Oxford colleges, a vicegerent is often someone appointed by the Master of a ...

, the deputy supreme head of ecclesiastical affairs. He created another set of institutions that gave a clear structure to the royal supremacy. Hence, the archbishop was eclipsed by Vicegerent Cromwell in regard to the king's spiritual jurisdiction. There is no evidence that Cranmer resented his position as junior partner. Although he was an exceptional scholar, he lacked the political ability to outface even clerical opponents. Those tasks were left to Cromwell.

On 29 January 1536, when Anne miscarried a son, the king began to reflect again on the biblical prohibitions that had haunted him during his marriage with Catherine of Aragon. Shortly after the miscarriage, the king started to take an interest in Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (c. 150824 October 1537) was List of English consorts, Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII of England from their Wives of Henry VIII, marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen followi ...

. By 24 April, he had commissioned Cromwell to prepare the case for a divorce. Unaware of these plans, Cranmer had continued to write letters to Cromwell on minor matters up to 22 April. Anne was sent to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

on 2 May, and Cranmer was urgently summoned by Cromwell. On the very next day, Cranmer wrote a letter to the king expressing his doubts about the queen's guilt, highlighting his own esteem for Anne. After it was delivered, Cranmer was resigned to the fact that the end of Anne's marriage was inevitable. On 16 May, he saw Anne in the Tower and heard her confession and the following day, he pronounced the marriage null and void. Two days later, Anne was executed; Cranmer was one of the few who publicly mourned her death.

The vicegerency brought the pace of reforms under the control of the king. A balance was instituted between the conservatives and the reformers and this was seen in the ''Ten Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

'', the first attempt at defining the beliefs of the Henrician Church. The articles had a two-part structure. The first five articles showed the influence of the reformers by recognising only three of the former seven sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the real ...

: baptism, eucharist, and penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of Repentance (theology), repentance for Christian views on sin, sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic Church, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox s ...

. The last five articles concerned the roles of images

An image is a visual representation of something. It can be two-dimensional, three-dimensional, or somehow otherwise feed into the visual system to convey information. An image can be an artifact, such as a photograph or other two-dimensiona ...

, saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual res ...

, rites

Rail India Technical and Economic Service Limited, abbreviated as RITES Ltd, is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Indian Railways, Ministry of Railways, Government of India. It is an engineering consultancy corporation, specializing in the field ...

and ceremonies, and purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

, and they reflected the views of the traditionalists. Two early drafts of the document have been preserved and show different teams of theologians at work. The competition between the conservatives and reformers is revealed in rival editorial corrections made by Cranmer and Cuthbert Tunstall

Cuthbert Tunstall (otherwise spelt Tunstal or Tonstall; 1474 – 18 November 1559) was an English Scholastic, church leader, diplomat, administrator and royal adviser. He served as Prince-Bishop of Durham during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edwar ...

, the bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

. The end product had something that pleased and annoyed both sides of the debate. By 11 July, Cranmer, Cromwell, and the Convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a speci ...

, the general assembly of the clergy, had subscribed to the ''Ten Articles''.

In late 1536, the north of England was convulsed in a series of uprisings collectively known as the Pilgrimage of Grace

The Pilgrimage of Grace was a popular revolt beginning in Yorkshire in October 1536, before spreading to other parts of Northern England including Cumberland, Northumberland, and north Lancashire, under the leadership of Robert Aske. The "most ...

, the most serious opposition to Henry's policies. Cromwell and Cranmer were the primary targets of the protesters' fury. Cromwell and the king worked furiously to quell the rebellion, while Cranmer kept a low profile. After it was clear that Henry's regime was safe, the government took the initiative to remedy the evident inadequacy of the ''Ten Articles''. The outcome after months of debate was ''The Institution of a Christian Man

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

'' informally known from the first issue as the Bishops' Book. The book was initially proposed in February 1537 in the first vicegerential synod, ordered by Cromwell, for the whole Church. Cromwell opened the proceedings, but as the synod progressed, Cranmer and Foxe took on the chairmanship and the co-ordination. Foxe did most of the final editing and the book was published in late September.

Even after publication, the book's status remained vague because the king had not given his full support to it. In a draft letter, Henry noted that he had not read the book, but supported its printing. His attention was most likely occupied by the pregnancy of Jane Seymour and the birth of the male heir, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, that Henry had sought for so long. Jane died shortly after giving birth and her funeral was held on 12 November. That month Henry started to work on the Bishops' Book; his amendments were sent to Cranmer, Sampson, and others for comment. Cranmer's responses to the king were far more confrontational than his colleagues' and he wrote at much greater length. They reveal unambiguous statements supporting reformed theology such as justification by faith or ''sola fide

''Justificatio sola fide'' (or simply ''sola fide''), meaning justification by faith alone, is a soteriological doctrine in Christian theology commonly held to distinguish the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, among others, fr ...

'' (faith alone) and predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

. His words did not convince the king. A new statement of faith was delayed until 1543 with the publication of the King's Book.

In 1538, the king and Cromwell arranged with Lutheran princes to have detailed discussions on forming a political and religious alliance. Henry had been seeking a new embassy from the Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

since mid-1537. The Lutherans were delighted by this and they sent a joint delegation from various German cities, including a colleague of Martin Luther's, Friedrich Myconius

Friedrich Myconius (originally named Friedrich Mekum and also Friedrich Mykonius) (26 December 1490 – 7 April 1546) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer. He was a colleague of Martin Luther.

Myconius was born in Lichtenfels ...

. The delegates arrived in England on 27 May 1538. After initial meetings with the king, Cromwell, and Cranmer, discussions on theological differences were transferred to Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposite ...

under Cranmer's chairmanship. Progress on an agreement was slow partly owing to Cromwell being too busy to help expedite the proceedings and partly because the negotiating team on the English side was evenly balanced between conservatives and reformers. The talks dragged on with the Germans becoming weary despite the Archbishop's strenuous efforts. The negotiations were fatally neutralised by an appointee of the king. Cranmer's colleague, Edward Foxe, who sat on Henry's Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, had died earlier in the year. The king chose as his replacement Cranmer's conservative rival, Cuthbert Tunstall, who was told to stay near Henry to give advice. On 5 August, when the German delegates sent a letter to the king regarding three items that particularly worried them (compulsory clerical celibacy, the withholding of the chalice from the laity, and the maintenance of private masses for the dead), Tunstall was able to intervene for the king and to influence the decision. The result was a thorough dismissal by the king of many of the Germans' chief concerns. Although Cranmer begged the Germans to continue with the negotiations, using the argument "to consider the many thousands of souls in England" at stake, they left on 1 October without any substantial achievements.

Reforms reversed (1539–1542)

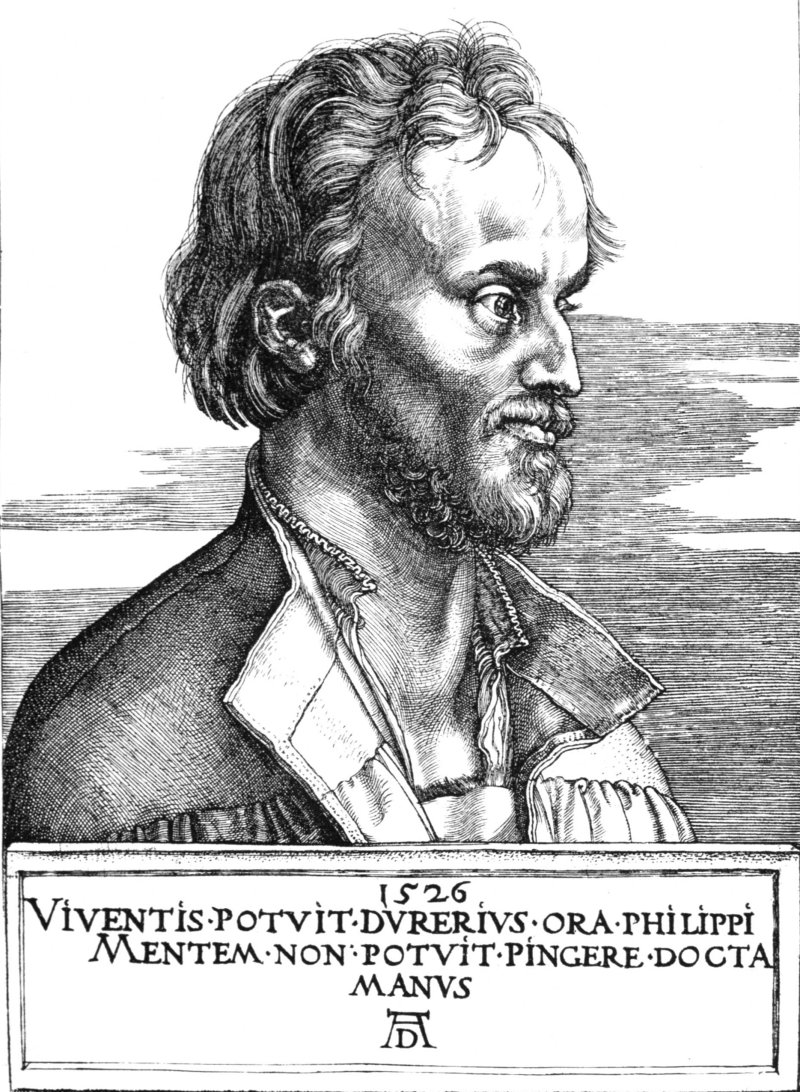

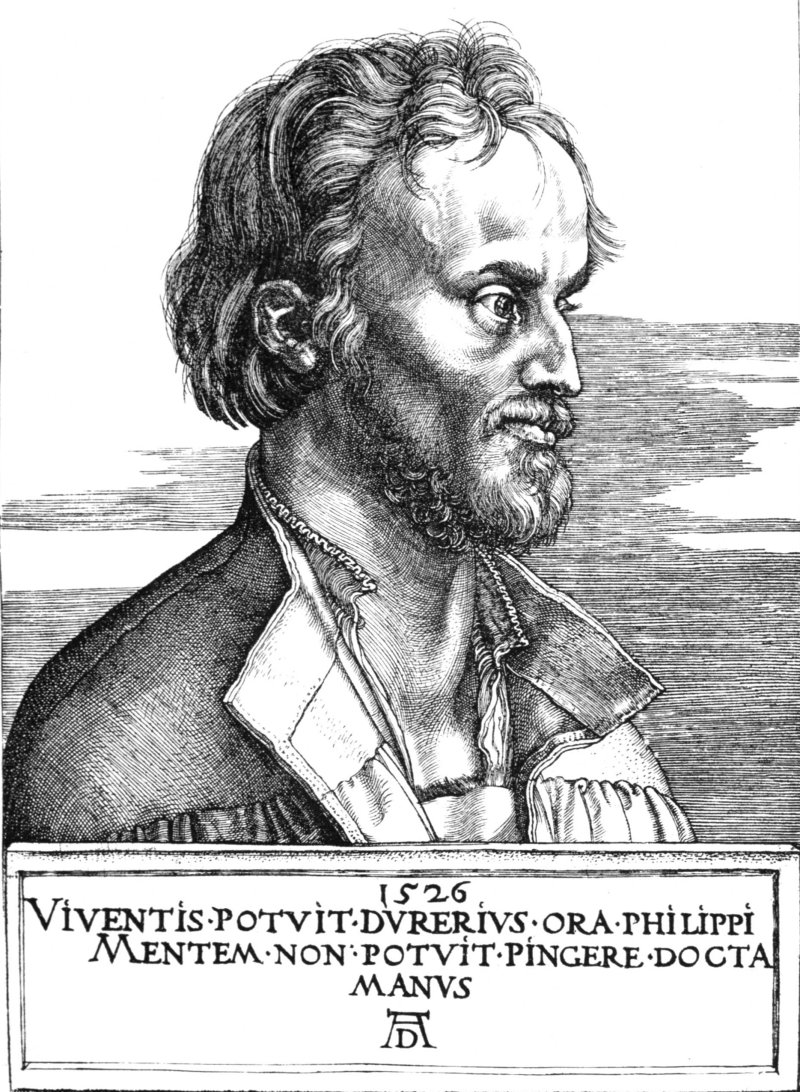

Continental reformerPhilipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

was aware that he was very much admired by Henry. In early 1539, Melanchthon wrote several letters to Henry criticising his views on religion, in particular his support of clerical celibacy. By late April another delegation from the Lutheran princes arrived to build on Melanchthon's exhortations. Cromwell wrote a letter to the king in support of the new Lutheran mission. The king had begun to change his stance and concentrated on wooing conservative opinion in England rather than reaching out to the Lutherans. On 28 April 1539, Parliament met for the first time in three years. Cranmer was present, but Cromwell was unable to attend due to ill health. On 5 May the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

created a committee with the customary religious balance between conservatives and reformers to examine and determine doctrine. The committee was given little time to do the detailed work needed for a thorough revision. On 16 May, the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

noted that the committee had not agreed on anything, and proposed that the Lords examine six doctrinal questions—which eventually formed the basis of the '' Six Articles''. They affirmed the conservative interpretation of doctrines such as the real presence, clerical celibacy, and the necessity of auricular confession, the private confession of sins to a priest. As the Act of the Six Articles neared passage in Parliament, Cranmer moved his wife and children out of England to safety. Up until this time, the family was kept quietly hidden, most likely in Ford Palace

Ford Palace was a residence of the Archbishops of Canterbury at Ford, about north-east of Canterbury and south-east of Herne Bay, in the parish of Hoath in the county of Kent in south-eastern England. The earliest structural evidence for t ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. The Act passed Parliament at the end of June and it forced Latimer and Nicholas Shaxton

Nicholas Shaxton (c. 1485 – 1556) was an English Reformer and Bishop of Salisbury.

Early life

He was a native of the diocese of Norwich, and studied at Cambridge, where he graduated B.A. in 1507. M.A. in 1510, B.D. in 1521 and D.D. in 1531. H ...

to resign their dioceses given their outspoken opposition to the measure.

The setback for the reformers was short-lived. By September, Henry was displeased with the results of the Act and its promulgators; the ever-loyal Cranmer and Cromwell were back in favour. The king asked his archbishop to write a new preface for the

The setback for the reformers was short-lived. By September, Henry was displeased with the results of the Act and its promulgators; the ever-loyal Cranmer and Cromwell were back in favour. The king asked his archbishop to write a new preface for the Great Bible

The Great Bible of 1539 was the first authorised edition of the Bible in English, authorised by King Henry VIII of England to be read aloud in the church services of the Church of England. The Great Bible was prepared by Myles Coverdale, worki ...

, an English translation of the Bible that was first published in April 1539 under the direction of Cromwell. The preface was in the form of a sermon addressed to readers. As for Cromwell, he was delighted that his plan of a royal marriage between Henry and Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves (german: Anna von Kleve; 1515 – 16 July 1557) was Queen of England from 6 January to 12 July 1540 as the fourth wife of King Henry VIII. Not much is known about Anne before 1527, when she became betrothed to Francis, Duke of ...

, the sister of a German prince was accepted by the king. In Cromwell's view, the marriage could potentially bring back contacts with the Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

. Henry was dismayed with Anne when they first met on 1 January 1540 but married her reluctantly on 6 January in a ceremony officiated by Cranmer. The marriage ended in disaster as Henry decided that he would request a royal divorce. This resulted in Henry being placed in an embarrassing position and Cromwell suffered the consequences. His old enemies, including the Duke of Norfolk, took advantage of the weakened Cromwell and he was arrested on 10 June. He immediately lost the support of all his friends, including Cranmer. As Cranmer had done for Anne Boleyn, he wrote a letter to the king defending the past work of Cromwell. Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves was quickly annulled on 9 July by the vice-gerential synod, now led by Cranmer and Gardiner.

Following the annulment, Cromwell was executed on 28 July. Cranmer now found himself in a politically prominent position, with no one else to shoulder the burden. Throughout the rest of Henry's reign, he clung to Henry's authority. The king had total trust in him and in return, Cranmer could not conceal anything from the king. At the end of June 1541, Henry with his new wife, Catherine Howard

Catherine Howard ( – 13 February 1542), also spelled Katheryn Howard, was Queen of England from 1540 until 1542 as the fifth wife of Henry VIII. She was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard and Joyce Culpeper, a cousin to Anne Boleyn (the se ...

, left for his first visit to the north of England. Cranmer was left in London as a member of a council taking care of matters for the king in his absence. His colleagues were Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley and Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford. This was Cranmer's first major piece of responsibility outside the Church. In October, while the king and queen were away, a reformer named John Lascelles

John Lassells (also Lascelles; died 1546) was an English sixteenth-century courtier and Protestant martyr. His report to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer initiated the investigation which led to the execution of Queen Catherine Howard.

Life

Lassells was ...

revealed to Cranmer that Catherine engaged in extramarital affairs. Cranmer gave the information to Audley and Seymour and they decided to wait until Henry's return. Afraid of angering the king, Audley and Seymour suggested that Cranmer inform Henry. Cranmer slipped a message to Henry during mass on All Saints Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are kno ...

. An investigation revealed the truth of the marital indiscretions and Catherine was executed in February 1542.

Support from the King (1543–1547)

In 1543, several conservative clergymen in Kent banded together to attack and denounce two reformers, Richard Turner and John Bland, before thePrivy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

. They prepared articles to present to the council, but at the last moment, additional denunciations were added by Stephen Gardiner's nephew, Germain Gardiner. These new articles attacked Cranmer and listed his misdeeds back to 1541. This document and the actions that followed were the basis of the so-called Prebendaries' Plot

The Prebendaries' Plot was an attempt during the English Reformation by religious conservatives to oust Thomas Cranmer from office as Archbishop of Canterbury. The events took place in 1543 and saw Cranmer formally accused of being a heretic. The h ...

. The articles were delivered to the Council in London and were probably read on 22 April 1543. The king most likely saw the articles against Cranmer that night. The archbishop appeared unaware that an attack on his person was made. His commissioners in Lambeth dealt specifically with Turner's case where he was acquitted, much to the fury of the conservatives.

While the plot against Cranmer was proceeding, the reformers were being attacked on other fronts. On 20 April, the Convocation reconvened to consider the revision of the Bishops' Book. Cranmer presided over the sub-committees, but the conservatives were able to overturn many reforming ideas, including justification by faith ''alone''. On 5 May, the new revision called ''A Necessary Doctrine and Erudition for any Christian Man

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

'' or the King's Book was released. Doctrinally, it was far more conservative than the Bishops' Book. On 10 May, the reformers received another blow. Parliament passed the Act for the Advancement of True Religion, which abolished "erroneous books" and restricted the reading of the Bible in English to those of noble status. From May to August, reformers were examined, forced to recant, or imprisoned.

For five months, Henry took no action on the accusations against his archbishop. The conspiracy was finally revealed to Cranmer by the king himself. According to Cranmer's secretary, Ralph Morice, sometime in September 1543 the king showed Cranmer a paper summarising the accusations against him. An investigation was to be mounted and Cranmer was appointed chief investigator. Surprise raids were carried out, evidence gathered, and ringleaders identified. Typically, Cranmer put the clergymen involved in the conspiracy through immediate humiliation, but he eventually forgave them and continued to use their services. To show his trust in Cranmer, Henry gave Cranmer his personal ring. When the Privy Council arrested Cranmer at the end of November, the nobles were stymied by the symbol of the king's trust in him. Cranmer's victory ended with two second-rank leaders imprisoned and Germain Gardiner executed.

With the atmosphere in Cranmer's favour, he pursued quiet efforts to reform the Church, particularly the liturgy. On 27 May 1544 the first officially authorised vernacular service was published, the processional service of intercession known as the ''

With the atmosphere in Cranmer's favour, he pursued quiet efforts to reform the Church, particularly the liturgy. On 27 May 1544 the first officially authorised vernacular service was published, the processional service of intercession known as the ''Exhortation and Litany

The ''Exhortation and Litany'', published in 1544, is the earliest officially authorized vernacular service in English. The same rite survives, in modified form, in the ''Book of Common Prayer''.

Background

Before the English Reformation, process ...

''. It survives today with minor modifications in the ''Book of Common Prayer''. The traditional litany

Litany, in Christian worship and some forms of Judaic worship, is a form of prayer used in services and processions, and consisting of a number of petitions. The word comes through Latin '' litania'' from Ancient Greek λιτανεία (''lit ...

uses invocation

An invocation (from the Latin verb ''invocare'' "to call on, invoke, to give") may take the form of:

*Supplication, prayer or spell.

*A form of possession.

*Command or conjuration.

*Self-identification with certain spirits.

These forms are ...

s to saints, but Cranmer thoroughly reformed this aspect by providing no opportunity in the text for such veneration

Veneration ( la, veneratio; el, τιμάω ), or veneration of saints, is the act of honoring a saint, a person who has been identified as having a high degree of sanctity or holiness. Angels are shown similar veneration in many religions. Etymo ...

. Additional reformers were elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

and new legislation was introduced to curb the effects of the Act of the Six Articles and the Act for the Advancement of True Religion.

In 1546, the conservatives in a coalition including Gardiner, the Duke of Norfolk, the Lord Chancellor Wriothesley, and the bishop of London, Edmund Bonner

Edmund Bonner (also Boner; c. 15005 September 1569) was Bishop of London from 1539 to 1549 and again from 1553 to 1559. Initially an instrumental figure in the schism of Henry VIII from Rome, he was antagonised by the Protestant reforms intro ...

, made one last attempt to challenge the reformers. Several reformers with links to Cranmer were targeted. Some such as Lascelles were burned at the stake. Powerful reform-minded nobles Edward Seymour and John Dudley

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Ja ...

returned to England from overseas and they were able to turn the tide against the conservatives. Two incidents tipped the balance. Gardiner was disgraced before the king when he refused to agree to exchange episcopal estates, and the son of the Duke of Norfolk was charged with treason and executed. There is no evidence that Cranmer played any part in these political games, and there were no further plots as the king's health ebbed in his final months. Cranmer performed his final duties for the king on 28 January 1547 when he gave a reformed statement of faith while gripping Henry's hand instead of giving him his last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. They may be administered to those awaiting execution, mortall ...

. Cranmer mourned Henry's death and it was later said that he demonstrated his grief by growing a beard. The beard was also a sign of his break with the past. Continental reformers grew beards to mark their rejection of the old Church and this significance of clerical beards was well understood in England. On 31 January, he was among the executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

s of the king's final will that nominated Edward Seymour as Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

and welcomed the boy king, Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

.

Foreign divines and reformed doctrines (1547–1549)

Under the regency of Seymour, the reformers became part of the establishment. A royal visitation of the provinces took place in August 1547 and each parish that was visited was instructed to obtain a copy of the ''Homilies''. This book consisted of twelve homilies of which four were written by Cranmer. His reassertion of the doctrine of justification by faith elicited a strong reaction from Gardiner. In the "Homily of Good Works annexed to Faith", Cranmer attacked

Under the regency of Seymour, the reformers became part of the establishment. A royal visitation of the provinces took place in August 1547 and each parish that was visited was instructed to obtain a copy of the ''Homilies''. This book consisted of twelve homilies of which four were written by Cranmer. His reassertion of the doctrine of justification by faith elicited a strong reaction from Gardiner. In the "Homily of Good Works annexed to Faith", Cranmer attacked monasticism

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role ...

and the importance of various personal actions involved in liturgical recitations and ceremonies. Hence, he narrowed the range of good works that would be considered necessary and reinforced the primacy of faith. In each parish visited, injunctions were put in place that resolved to, "...eliminate any image which had any suspicion of devotion attached to it."